Inflation is WAYYY Down. Yay!

Inflation has been cut in half—and then some—since June of last year.

Remember when Ronald Reagan declared “Morning in America”? The years before were dark. And in the darkness raged the storm of stagflation.

The sharknado of the economics world, stagflation is a combination of two frightening things: a stagnant economy (i.e. slow growth and high unemployment) and high inflation.

In the spring of 1980, inflation peaked near 15 percent. And, in the fall of 1982, unemployment peaked near 11 percent. The misery index, which adds up the inflation and unemployment rates, reached a high of almost 21 percent in 1980.

On the basis of this plagued economy, Jimmy Carter, who held the presidency from 1977 through 1981, was summarily routed in the 1980 election. Reagan took office, and by the time of his re-election in 1984, the misery index had been just about cut in half from its level four years earlier. Most critically, inflation had fallen substantially.1 Things were looking so good that the Reagan campaign put out an ad, destined to become one of the most famous election ads of all time, declaring victory: “It’s morning again in America.”

Now, fast forward four decades. Joe Biden is president, and inflation is at a lower level than when Reagan announced “Morning in America.”2 In fact, inflation is down by almost five percentage points from its June 2022 peak. Most remarkably, unlike in the early 1980s when the Fed’s campaign against inflation led to a sharp spike in unemployment, during this round the unemployment rate has held steady at a historically low level. Consequently, the misery index is a solid 6.6 percentage points below its 1984 level.3 Hello sunshine.

How far has the inflation fight come?

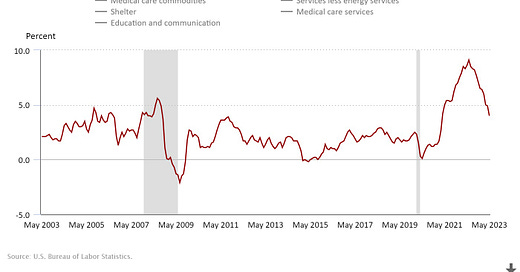

Different measures of inflation give different pictures of how far the inflation fight has come. If we look at the headline figures, which are meant to gauge overall inflation, for both the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) price index, we see substantial drops in inflation over the last year.

Here’s CPI:

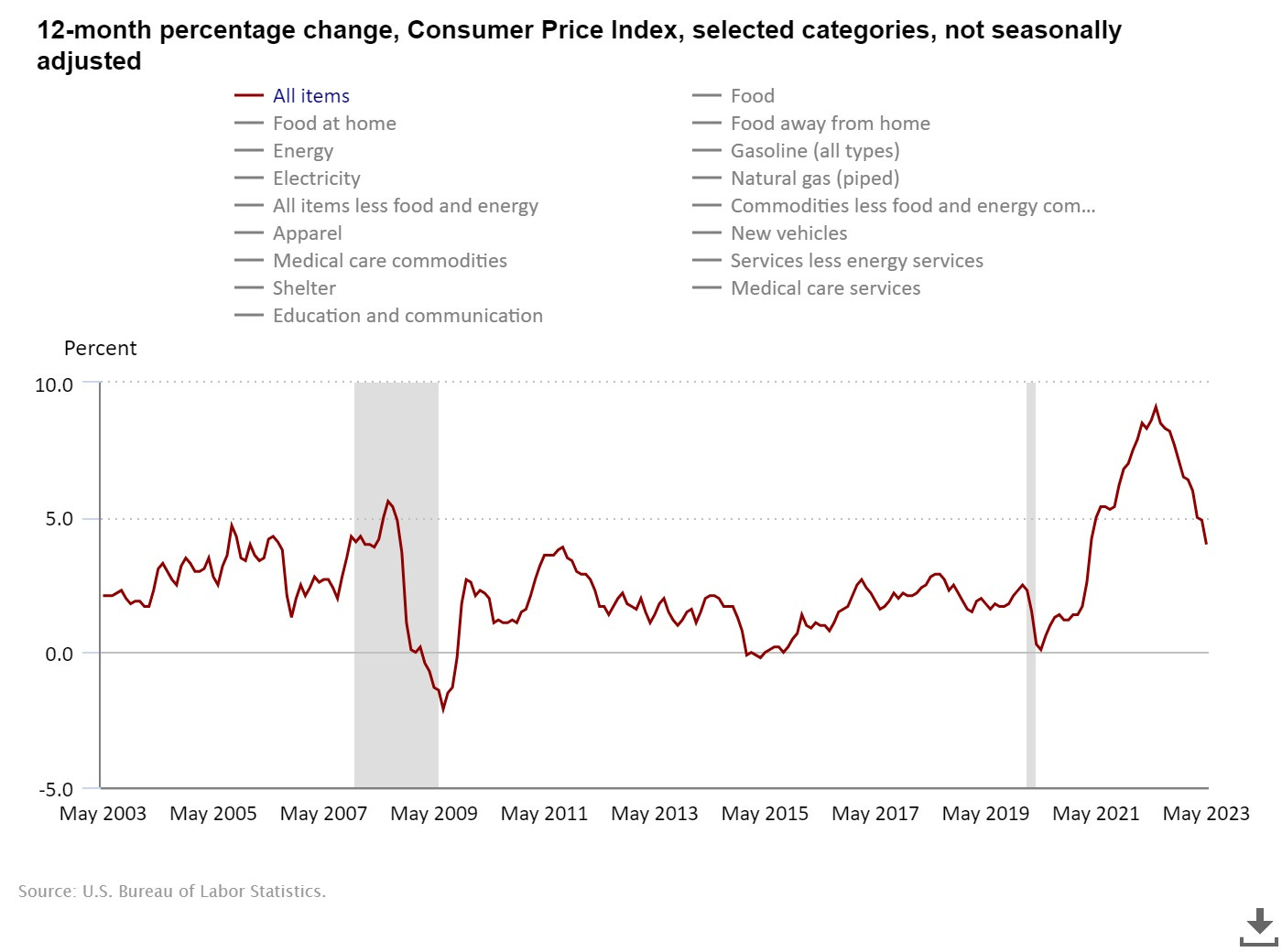

If we look at core inflation, which strips out the more volatile food and energy categories, we get a less rosy picture.

Here’s core CPI:

And here’s core PCE:

At a basic level, when we’re thinking of the impact that inflation has on ordinary people, we should be looking at the headline figures, not the core figures. After all, food and energy costs are fundamental components of the average person’s expenses, and ones that are at the top of people’s minds. Just look at how well Biden’s polling numbers correlated with gas prices in the run-up to the midterm elections.

The utility of looking at core is to see what’s going on with the more durable parts of inflation. Energy and food prices are prone to temporary blips, where they quickly rise and fall, but prices for other categories may start rising faster in a more lasting way. This could suggest generalized overheating (excess overall demand), which the Fed might want to stamp out by raising interest rates.

The problem lately, though, is that elements within core inflation have experienced temporary price spikes, suggesting the rise in core inflation has reflected sector-specific issues rather than the sort of generalized overheating that interest rate hikes are built to address. Used car prices, for instance, have fluctuated like crazy in the face of supply chain snarls. As Bloomberg notes, “Even though used cars make up less than 3 percent of the Consumer Price Index, the monthly changes have been so large that at times they’ve been the main story”:

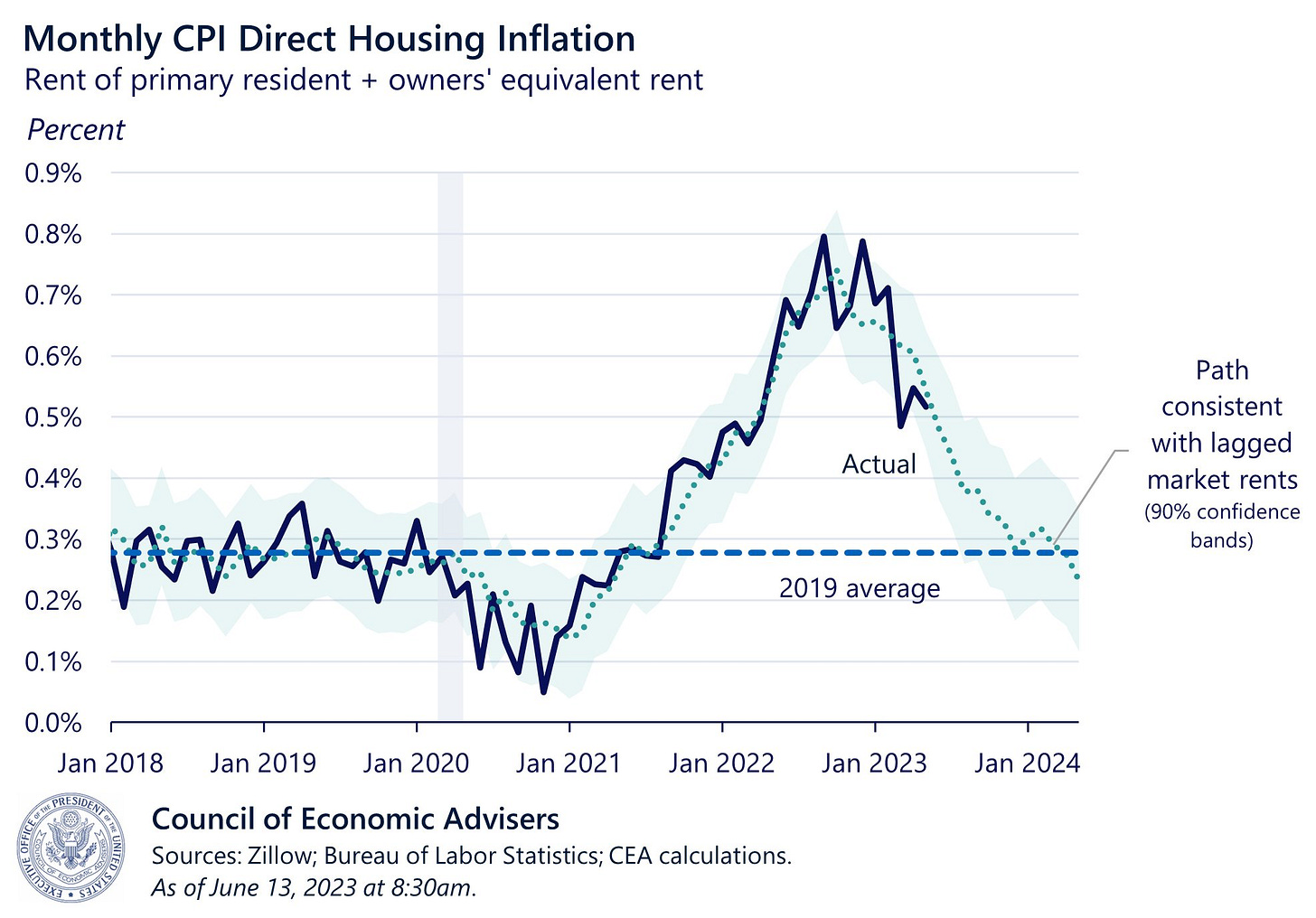

Rents likewise saw a temporary spike in the midst of the pandemic. As Paul Krugman writes in a recent column, “There was a huge surge in rents between 2021 and early 2022, probably driven by the rise in remote work.” And, because rents are measured based on all existing leases rather than just new leases, this surge is still having a major impact on inflation data. (Housing costs account for around 40 percent of core CPI, and they are determined to a large degree by rents.5)

As the effects of the mid-pandemic surge in rents on measured rental inflation subside, housing inflation will fall (as it has already started to). So a major reason core inflation looks worse than headline right now is that it’s measuring past rents, which were increasing more rapidly than usual due to a transitory blip.

In light of how much the core measure is currently capturing what the non-core measure is meant to capture—temporary and sector-specific price spikes—Krugman has pronounced core inflation “rotten.” He prefers to instead go “supercore” by excluding the recently volatile used car and housing components in addition to the energy and food components. Looking at this measure, we see clear disinflation:

But why?

At first glance, you might think: Wow, the Fed is crushing it in its war against inflation. But, in reality, the story isn’t so much that the Fed is killing it. It’s more that the enemy is cannibalizing itself.

The Fed’s preferred inflation-fighting maneuver is the interest rate hike. That works by dampening demand in the economy, preventing consumers from being able to support such rapid increases in prices. But the main driver of inflation has been supply issues, an area where the Fed is impotent (it can’t create more oil or food or cars). And the resolution of these supply issues has likewise been the key driver of disinflation.

As the above graph makes clear, the supply-driven contribution to inflation is coming down at about the same speed that it went up. The demand-driven contribution, meanwhile, is barely below its peak. You can make out a bit of a decline, but nothing as stark as on the supply side.

If we zoom in on core inflation, we see a similar story.

As Joey Politano has detailed, supply chains are healing. Only four input commodities remain in short supply, down from over 35 a couple years ago. And far fewer US manufacturers are citing supply-side constraints compared to a year-and-a-half ago.

That’s not to say that the Fed’s campaign of interest rate hikes has not helped bring down inflation, just that it’s not the primary reason for this development. According to the economist James Galbraith,

The Fed’s policies did have some effect. They stalled construction (briefly) and halted a real estate boom, affecting the Consumer Price Index mainly through the exaggerated impact of homeowners’ imputed rent. Since imputed rent is a statistical chimera [it’s metric for indirectly estimating housing prices, not a price anyone actually pays6], why this is sensible public policy is a mystery. Apart from that, there is no channel from interest rates to consumer prices, short of major effects on the dollar or the whole economy — neither of which have yet occurred.

So basically, the Fed put the brakes on the Consumer Price Index by preventing home prices from continuing to skyrocket, popping what was “(largely) an asset bubble.”

Where do we go from here?

In Galbraith’s view, recent disinflation demonstrates “that the price increases of 2021–2022 were in fact mostly transitory.” Which doesn’t mean that elevated inflation has been conquered. For one, energy prices could rise again. And interest rate hikes, which dampen investment, are making us only more vulnerable to such a price shock.

Moreover, high profit margins (not wage growth, as some have worried) could pose an ongoing issue, keeping inflation elevated. As Galbraith writes,

In normal times, margins generally remain stable, because businesses value good customer relations and a predictable ratio of price to cost. But in disturbed and disrupted moments, increased margins are a hedge against cost uncertainties, and there develops a general climate of “get what you can, while you can.” The result is a dynamic of rising prices, rising costs, rising prices again — with wages always lagging behind.

The solution he advocates to this problem is not interest rate hikes but price controls. These break the cycle of profit-driven inflation by preventing companies from pushing prices higher and higher:

Their effect, if properly done, is to restore the normal climate of expected stability and good behavior, so that business managers are induced to focus, as they should, on quality and quantity rather than price.

A sensible approach to inflation would have considered price regulation from the start. The economists J.W. Mason and Lauren Melodia, for instance, advocated this type of policy in a brief for the Roosevelt Institute in late 2021, shortly before the Fed began raising interest rates.7

But probably the best we can hope for at the moment is for the Fed to stop raising rates, which, to its credit, it finally did this month. With inflation already down substantially, let’s hope the pause holds. The risk of more tightening—whether to the banking sector or to the unemployment rate—is really not worth the reward.

Bonus fun

This meme from New York Times reporter Talmon Joseph Smith beautifully captures the absurdity of focusing on core inflation right now:8

Subscribe!

If you enjoyed this post, please subscribe! You will be notified when my posts go up and will have the newsletter delivered directly to your inbox.

And share!

And please share! I’m building this newsletter from the ground up, so everything helps.

Share this post:

Share Objective Propaganda:

Other Recent Writing

Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting:

“WaPo Mad That Debt Ceiling Deal Didn’t Cut Social Security” (6/15/23)

“WSJ Celebrates Making It Harder for Poor People to Access Food” (6/9/23)

“WSJ Says Corporate Profiteering Is Good, Actually” (6/1/23)

Current Affairs:

“Pandemic Social Spending Was a Remarkable Success That Showed What Authentic Social Democracy Could Be Like” (6/2/23)

Unemployment in fact was basically unchanged from its November 1980 level in November 1984, sitting at 7.2 percent versus the 7.5 percent rate it registered four years before. Inflation, by contrast, had fallen from 12.6 percent to 4.2 percent over this period.

4.1 percent now versus 4.3 percent then.

7.8 percent as of May versus 14.4 percent in the month Reagan’s ad premiered.

The Fed aims for 2 percent headline PCE inflation “over the longer run.” This target has been contested by very mainstream observers, who think a bit of a higher target would be perfectly fine.

Rents themselves made up about a fifth of the housing component of CPI in December 2022, but they are also used to calculate home prices, so rental prices have a much larger impact on measured housing inflation than their weight in the measure suggests. The home prices measure is called owners’ equivalent rent (OER), and it accounted for about three-quarters of the housing component of CPI in December 2022. Krugman says that this measure “is basically derived from average rents.”

As J.W. Mason wrote after the Fed began raising rates in early 2022, “It’s worth noting that a significant and rising part of recent inflation is owners’ equivalent rent, which is a survey-based measure of how much homeowners think they could rent their home for. It is not a price paid by anyone. Meanwhile, mortgage payments, which are the main housing cost for homeowners, are not included in the CPI. It’s a bit ironic that in response to a rise in a component of ‘housing costs’ that is not actually a cost to anyone, the Fed is taking steps to raise what actually is the biggest component of housing costs.”

Todd Tucker also wrote about price controls around the same time for the Roosevelt Institute.

Relevant to the last part of this meme, I’ll probably talk about the Fed’s 2 percent inflation target in a future post.