Taxes Are Not An Artificial Imposition on Your Rightful Income

Americans' thinking about taxes is confused.

Hatred of taxes is widespread. But taxes are misunderstood.

The market is not natural. And the government does not exist outside of it. Taxes are not an artificial imposition on a natural market. They are simply one of many tools for shaping the income distribution.

Does that all make sense? If not, hopefully by the end of this piece it will.

Confused Thinking About Income

When people think about their income, they often seem to think that they basically deserve what they earn in the market—if anything, they think they deserve more. So when the government pops in to confiscate some of that income, people see that as an interference with their natural income, what is rightfully theirs.

Is that market income actually your true/natural income, though? I suppose if we lived in an idealized perfectly competitive market economy you could answer yes. But we don’t live in a textbook. We live in the real world.

Here in the real world, markets are imperfectly competitive. Wages at the bottom are depressed because employers hold power over workers. Wages at the top are inflated because those at the top have written the rules of the economy in their own favor.

Developments such as the erosion of union power and a fall in the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage over recent decades have fundamentally reshaped the market. The result has been functionally equivalent to redistribution through taxation, but this redistribution has occurred away from the very visible hand of government taxation and therefore doesn’t appear as artificial as the sort of redistribution that government taxation directly facilitates.

Suresh Naidu, Eric Posner, and Glen Weyl made this point in a Vox article a few years back. As they put it,

Wage suppression is just like a tax: a tax on the labor of workers. But unlike most taxes, the proceeds do not fund public services or redistribution that benefits the vulnerable. Instead, they fund corporate profits and cause the share of income accruing to workers to fall. (That share has fallen almost 10 percent in the US in the past decade). This fall in labor income and rise in profits have fueled the remarkable rise in the incomes of the top 1 percent of earners about which so much has been written.

Naidu, Posner, and Weyl estimate that this hidden tax has depressed median compensation by as much as $61,500:

For the labor market as a whole, the median annual compensation is $30,500. If markets were competitive, we estimate that this amount could rise to $41,000, and possibly to as much as $92,000.

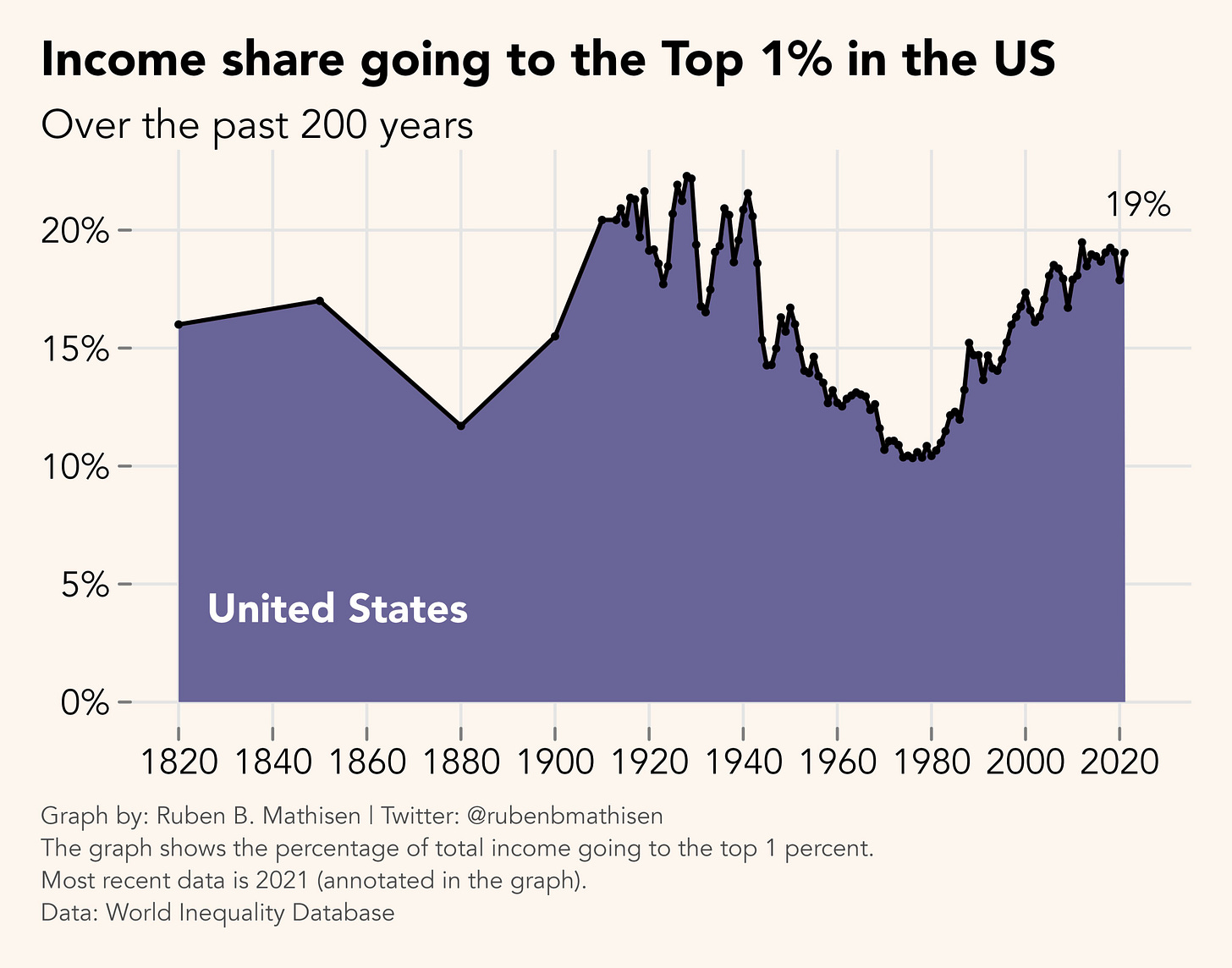

The flip side of the suppression of lower- and middle-incomes is, of course, the surge in top incomes, both in absolute terms and as a share of total income:

This rise in inequality was not inevitable. It was the result of deliberate policy decisions.

Another estimate of how much the rise in inequality has reduced incomes at the middle of the distribution comes from the Economic Policy Institute, a progressive think tank. It has termed the hidden within-market tax discussed by Naidu, Posner, and Weyl an “inequality tax.” As shown in the following graph, this tax has substantially curbed middle class income growth:

According to EPI, the rise in inequality from 1979 through 2007 depressed the average annual income of middle-income families by about $20,000 in 2007. That’s a 27% inequality tax on these households.

There’s no material difference for this group between this reality and an alternative scenario in which inequality remained stable and government taxes were increased by 27%. Middle-income families would have ended up with the same after-tax income.

For a person who thinks of the market as natural and the government as existing outside of the market, however, the inequality tax passes under the radar. It’s not thought of as an artificial imposition in the same way that a tax levied directly by the government is.

Taxes Are Not the Only Way to Structure the Distribution of Income

A government tax, then, is just one way of tinkering with the income distribution. It’s one tool in a toolkit. There are other tools, such as the minimum wage and pro-union legislation, that will affect the income distribution as well, and will specifically impact market incomes, exactly the incomes that many people seem to imagine are natural, basically detached from the government’s dirty hands.

If we appreciate the government’s power in structuring market incomes, we can see how silly it is to think of the salary we earn from our jobs as the income that is rightfully ours.

After all, our income from our jobs and our income after taxes are both determined by government to some degree: Our market income is the income we’ve been able to earn within the constraints of some government policies, while our after-tax income is what we’ve been able to earn within the full constraints of government policies.

If you think one form of income is rightfully yours and the other has been artificially reduced due to government meddling, you’re living in fantasy land. Both are artificial. Neither are necessarily what you deserve.